Context

The development of recreational practices is now leading to an increasing human presence in natural areas (Mao et al. 2009; Zeidenitz et al., 2016) and particularly in protected areas. This presence can be a major source of disturbance for wildlife, leading to a series of modifications (Marchand et al. 2014, 2017), with potential cascading consequences on ecosystems (Geffroy et al. 2015). However, combining biodiversity conservation and tourism development as well as different types of outdoor activities (e.g., hunting and non-consumptive activities) can be conflicting (Reis & Higham, 2009), requiring a better understanding of socio-ecosystems from both the social and human sciences and ecology (Knight & Gutzwiller, 1995; Depraz, 2008). This involves better understanding the effects of human presence on wildlife and understanding the expectations, attitudes, and perceptions of recreationists towards nature, wildlife, and use restrictions (Zoderer et al., 2016).

Communication proposals from the humanities and social sciences, environmental sciences and management may fall under one of the following three axes.

Axis 1: Recreational practices in nature and their relationship to the invested environments

In this first axis, we expect to see work that analyzes recreational practices in nature, from their socio-spatial characteristics to the types of relationships that these practices allow with the environment and its wildlife.

In line with work conducted in sports sociology and geography (Lapierre, 1981; Jorand, 2000; Jallat, 2001; Corneloup, 2003; Lefèvre, 2004; Guyon, 2013), papers will highlight different ways of practicing the same sport/activity (including hunting and fishing), study the relationship of nature sports practitioners to the territory where the activity takes place (Brymer and Gray, 2009; Humberston, 2011; Féménias et al, 2011; Baticle, 2007 and 2013), or to take an interest in the mobilities/routes of practitioners in space. Nature sports and nature-based recreational activities offer a particular access to territory where the body takes a central place (Chanvallon and Héas; 2011). As shown by Niel and Sirost (2008), by actively living the space and becoming one with it, the sportsmen leave the contemplative dimension in favor of a moving and carnal dimension in which all the senses are mobilized. It is also a question of questioning the relationship that recreational activities practitioners have with the invested environment and wild animals. Papers may question the place of the animal presence in the landscape perceptions of the territory and/or focus on the perception of wildlife disturbance by different recreational users (Le Corre et al., 2013; Sterl et al., 2008; Taylor and Knight, 2003).

Axis 2: The cohabitation between human presence and wild animals

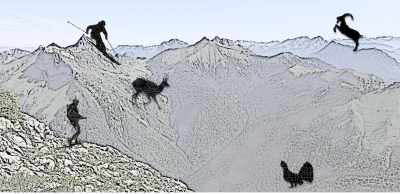

In this axis, we expect papers that address the issue of how humans and animals live together in natural spaces. Papers will be able to deal with the consequences of human presence on the location, behavior, and physiology of animals, but also to discuss possible collaborations or ways of living together between those who practice recreational activities in nature and wild animals.

By being present in the wildlife landscape, humans modify the "risk" value of the different places where the animals could go. The concepts of "risk landscape" and "fear landscape" have been developed in behavioral ecology and landscape ecology to formalize the fact that an animal lives in a space that it perceives both in terms of food resources, but also in terms of feelings related to the likelihood of being disturbed or killed (Altendorf et al., 2001; Laundré et al., 2001). Thus, in certain cases, and depending on the activities carried out and the number of people present (Enggist-Dûblin and Ingold, 2002), the presence of humans can be considered a factor in the degradation of the habitat of wild animals (Knight and Gutzwiller, 1995), having direct and indirect impacts on the survival of the fauna; on the other hand, it can also be sought after by certain animals through habituation or even attraction phenomena, in order to find food resources more easily. On the other hand, the presence of animals can have an impact on the experience of the participants. Depending on the time of day, the species encountered, the circumstances of the encounter, the practice carried out, the experience of nature of a practitioner will be plural.

Axis 3: Management methods for recreational practices and user awareness

In this area, work is expected on the environmental management of recreational activities in nature and on the reception of these management measures by users.

If at the beginning, the development of nature sports mainly generated conflicts of use (Jacob and Schreyer, 1980), these conflicts were coupled with environmental conflicts when their impact on the environment began to be questioned. For protected areas, the environmental management of nature sports poses real problems. On the one hand, in most cases, it is difficult to identify the impacts, other than potential, of these activities (Mounet, 2007a). On the other hand, the evolution of environmental sensitivities and ethics has led the world of environmental protection to move away from a bio-centric vision (Larrère, 1997), which was built in response to the unlimited use of natural resources. It is now accepted that humans are part of nature, even in spaces with regulatory prerogatives. The management of visitor flows is an increasingly important issue in relation to the conservation objectives of the area, and it is not feasible to use prohibition as the only management tool, as this may prove to be a failure (Mounet, 2007b).

In some areas, campaigns to raise awareness of the fragility of the wildlife and the environment have been implemented. However, these conservation measures are not always successful. For example, the installation of barriers and prohibition signs does not seem to have any effect on the behavior of users who have already chosen their route (Immoos and Hunziker, 2015) and these measures are often perceived as restricting their freedom (Hender et al. 1990).

Communication proposals can be of two kinds.

They can present academic research in an oral presentation format. The abstract (4,000 characters) should then indicate the axis in which the paper wishes to be placed, the theoretical framework, the problematization, the methodology used as well as the results and discussions.

One day of the conference will be devoted to exchanges between academics and managers (PNR, National Parks, OFB, hunting federations). Proposals may also propose other types of exchange formats (round table, workshop, film session). The abstracts should then present the proposed format, the type of interventions envisaged and the problematic treated.

Papers on interdisciplinary work are encouraged. They can be in French or in English. They must be submitted by October 15, 2022.